Plateaus – aka periods of little to no progress – are inevitable in the sport of weightlifting.

It’s the nature of any sport that is so neurological in nature. What I mean by neurological is that it’s very technical. An athlete can increase his or her squat by 10kg/22lb and experience zero increase in the snatch and clean and jerk. If an athlete experiences a glitch in positioning, it won’t matter how much force or velocity one applies.

This is the very trait that makes weightlifting like baseball, golf, and tennis. People go into a slump due to multiple possibilities like CNS fatigue, accommodation, asymmetries, dysfunctional motor patterns, muscular weakness, and legitimate mental blocks. Plateaus can happen in powerlifting, strength and conditioning, and CrossFit – but they should be a bit easier to overcome. Regardless, you will be able to use the following principles to help you or your athletes overcome plateaus. One thing we don’t do is follow the old school advice of “stick with what you’re doing and eventually you will come through it.” No way, we fight plateaus like someone drowning and doing anything they can to get that last breath of air. We fight it!

Causes and Contributors

CNS Fatigue is quite a different animal than PNS Fatigue. Peripheral Nervous System fatigue is a necessary part of the training process to encourage adaptation. Athletes want to stress the muscles, tendons, ligaments, and even bones to stimulate a positive response from the body. However, we want to keep our CNS (Central Nervous System) flowing as close to normal as possible.

Some of the first questions that I ask an athlete who is struggling to improve are:

- Is your sleep affected?

- Is your appetite affected?

- Is your overall mood altered?

CNS Fatigue will disrupt sleep, cause a lack of appetite, and will cause an athlete to be irritable. Why?

CNS Fatigue carries with it a change in the predominant neurotransmitters of the body. When the body is recovered and stress-free, dopamine and serotonin flow freely throughout the CNS. This allows action potentials to flow across the synaptic clefts at the junction of nerves to other nerves, muscles, and tissues. Dopamine is responsible for learning, coordination, feelings of reward and satisfaction, and motivation. Serotonin is responsible for promoting good sleep, appetite regulation, learning, and social behavior. CNS fatigue is caused from too much stress, which keeps the sympathetic nervous system cranking.

CNS Fatigue disrupts an athlete’s ability to coordinate movement, interpret instruction, and eventually affects the ability to recover in general due to lack of sleep and nutrition. It simply spirals more and more out of whack until the athlete takes control of the situation. The good thing about velocity based training is that a coach can identify CNS fatigue by tracking the velocity of different exercises at corresponding percentages. When the velocity of a percentage is more than 10% slower than the normal velocity, CNS is probably the culprit. Here are some steps to take:

- Stopping any complex movements and immediately moving into some low intensity and higher repetition bodybuilding with a focus on metabolic stress to encourage a positive hormonal response (testosterone, GH, IGF1, etc)

- A drop in load and overall volume in the following days by 10-20% until sleep and appetite return to normal

- Meditation, prayer, and other stress relievers

- Massage

- Breath work

- Learning to manage stress with a professional counselor

If it’s not CNS Fatigue, the next logical answer is accommodation. If you are a Louie Simmons fan, then chances are you’ve heard him talk about the Law of Accommodation – “Zatsiorsky stated that the response of a biological object to a given constant stimulus decreases over time.” Now in weightlifting, we can’t make the drastic alterations to our training stimuli due to the neurological complexity of the movements contested. Powerlifting is slower movements with two simple phases, but Olympic weightlifting is multi-directional and relies heavily on the agonist-antagonist relationship – much like swinging a bat in baseball. Put simply, if you want to get better at snatch and clean and jerk, then you better have snatch and clean and jerk in your program. That doesn’t mean there aren’t several aspects that can be manipulated. Let’s look at each of them:

Areas to Manipulate

- Total Volume and Average Intensity

- K Value

- Relative Intensity

- Optimal Number of Lifts

- Frequency

- Exercise Selection

- Accessory Work

- Velocity Based Training

- Tempo (including pauses)

Total Volume and Average Intensity – The average intensity is found by tracking the total volume and the total number of reps in a workout or training cycle depending on what you are figuring for. That’s why we are discussing total volume and average intensity together. Total volume is found by multiplying the number of reps x the load for each set and then adding all the sets together. Example:

Set 1 100kg x 3= 300kg

Set 2 110kg x 2 reps = 220kg

Set 3 120kg x 1 rep = 120kg

Total volume= 300kg+220kg+120kg= 640kg

We track the total volume for all of the competition lifts and the primary accessory lifts (back squat, front squat, clean pulls, snatch pulls, jerks, power jerks, push press, etc). It’s good to track all of these together, and to keep them separate. By keeping them separate, you can track where you focused the majority of your time. We will go over this a bit more when we discuss the optimal number of lifts.

To find the average intensity, you simply divide the total volume by the total number of reps. In the example above, the total volume is 640kg and the total number of reps is 6. Therefore, you would divide 640kg by 6 (640kg/6= 106.67), which equals 106.67 rounded up to 107kg. It’s important to track this number for entire macrocycles, mesocyclyes, and microcycles. Why is data important? Let’s say an athlete is experiencing CNS fatigue, plateauing, and going backwards. We need to be able to compare total volume of macrocycles (bigger phases of a planned out program example offseason, preseason, etc), mesocycles (normally four week blocks with specific adaptations planned), and microcycles (smaller cycles within mesocycles usually one week) with other cycles. Then you can see increases in volume and average intensity, and hopefully pinpoint the breaking point. It’s good to look at your microcycles ahead of time to make sure that the increased stimulus is slow and steady versus a major shock to an athlete’s system. If you’re not tracking data, then you are just guessing.

On the other hand, it’s important to track the total volume and average intensity to put values on success. If an athlete experiences a 10kg improvement in their total, it’s important to realize that this improvement was experienced with 750,000kg of total volume over a 12 week period with an average intensity of 107kg. Then you can use our next data point to plan your next phase in hopes of continued improvement. Let’s look!

K Value – Bob Takano popularized this data point in America after learning this coefficient from Carl Miller in 1974. Professor Angel Spassov also discussed the K Value during his American tour discussing the training practices of the Bulgarians. I will mention this a bit more at the end of this section.

Here’s what you need to figure the K Value:

- Total Load (total volume) of a competition macrocycle (usually 12-20 weeks)

- Total number of reps

- Total achieved (needs to be a successful training macrocycle)

I explained above how to figure the total load aka total volume. Let’s say that your total volume for a 12-week training block is hypothetically 800,000kg and your total number of reps is 7,000. And let’s suppose you make a total of 320kg in your meet. Here’s how you figure the K Value:

- K Value= (Average Intensity x 100)/proposed total

- Total Volume divided by the total number or reps (800,000kg/7,000reps)= average intensity of 114kg

- Average Intensity x 100, so 114kg x 100= 11400

- To find the K Value divide 11,400 by the 320kg successful total(11,400/320= 35.6)

Now it’s time to use the K Value to plan the next phase of training by multiplying a goal total by the K Value. If our goal becomes to total 330kg, you would multiply 330kg x .356 (K Value is actually a percentage so 35.6 becomes .356) equaling 117.48 rounded to 118kg. Your average intensity will need to become 118kg over your next training block to potentially total 320kg.

Relative Intensity – This is a bit more complicated to track, but important nonetheless. Here’s how a coach can figure out an athlete’s Relative Intensity (RI). RI is figured by taking (the weight an athlete is using for a particular number of reps)/(the maximum weight that athlete can perform in that given rep range). Let’s use an example:

Athlete 1 has a 5-repetition maximum of 400lb in the bench press, and is benching 350lb for sets of 5 reps.

350/400=87.5% so the relative intensity is 87.5%

The coach or athlete will need to know the repetition maximums of each exercise in all of the different repetition ranges. Just like tracking average maximal intensity, it’s also important to track an athlete’s ongoing average relative intensity in a macrocycle, mesocycle, and microcycle. To do that, the athlete would need to track the relative intensity of each set divided by the total sets. Let’s look at an example:

Set 1 300 x 5 with a 5rm of 320 (relative intensity of 94%)

Set 2 320 x 3 with a 3RM of 335 (RI 96%)

Set 3 330 x 2 with a 2RM of 345 (RI 96%)

Average RI of the workout would be (94%+96%+96%)/3= RI of 95%

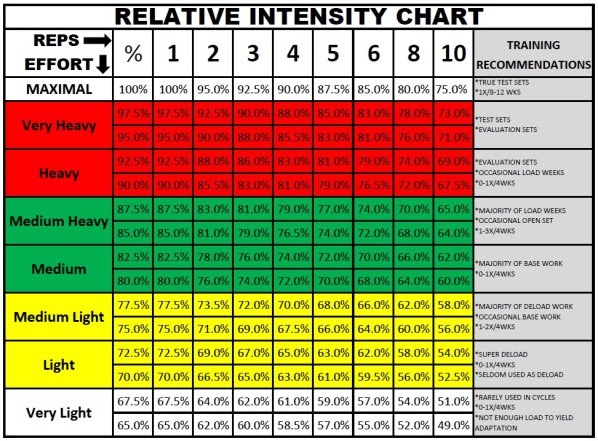

Here’s a chart showing you where to spend most of your time:

Just like total volume and average intensity, the coach or athlete can look at the relative intensity to put a value on whatever is happening. If an athlete’s average intensity is 83% and they’re experiencing lots of progress, they’re on the right track. On the other hand, if an athlete is going backwards or plateauing with an average intensity of 88%, they can make a decision to increase or decrease that RI. Based on the chart above, the wise decision might me to decrease it just a bit.

[thrive_leads id=’11558′]

Optimal Number of Lifts –

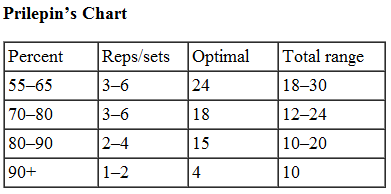

It’s important that an athlete or coach understands Prilepin’s Chart for this next data point. Here’s a look:

It’s important that a coach or athlete tracks the optimal number of lifts in three different categories:

- The Competition Lifts: Snatch and Clean & Jerk

- Variations of the Competition Lifts: Powers, hangs, blocks, jerk from blocks/rack, power jerk, or anything resembling the competition lift.

- Absolute Strength Category: Squats, Pulls, Deadlifts, Push Press, Strict Press, or relative accessory movements.

It’s important to know the optimal number of lifts (ONOLs) performed in each category to get an idea where an athlete is spending their time. Obviously category number one is the most important. However, for most category number 3 is just as important or more important. Category 2 is used to target specific movement or velocity flaws. I recommend dividing total training over a macrocycle like the following:

- ONOLs in the Competition Lifts 40% of total ONOLs

- ONOLs in the Squats, Deadlifts, Push Press, etc (category 3) 40% of total ONOLs

- ONOLs in the variations of competition lifts (category 2) 20% of total ONOLs

Then consideration can be made for efficient athletes needing strength, and for incredibly strong athletes needing more focus in the competition lifts and their variation. A coach could consider putting more focus in one category over another, but the key is going to be tracking the data. That’s the message. If an athlete is performing 50% of their total optimal number of lifts in the competition lifts and experiencing a plateau, he or she might consider allocating a higher percentage of their ONOLs to the strength movements.

Frequency – This is referring to how often an exercise is used day to day and week to week. This is my go to training characteristic to manipulate if an athlete is experiencing a plateau in any category. If their snatch is stagnant, I recommend increasing the frequency of the snatch. If his or her squat isn’t moving, squat every dang day baby until it is moving. Obviously, it’s really hard for a drug free athlete to perform any movement day in and day out without experiencing overuse injuries. Therefore, I recommend using this protocol in 4 to 12 week blocks followed by higher volume density training.

Exercise Selection – If an athlete is experiencing a plateau, eventually exercise selection becomes a consideration. For example, I just had an elite weightlifter experience his first bit of a plateau and actually a slight decline. This happened right before the Senior National Championships, which was also the final tryout for the Junior World Team and Senior Pan American Team. So did I stick to the plan and hope for the best? Nope, I rapidly switched to accommodating resistance in the squats and pulls in hopes of exciting the nervous and triggering a positive adaptation. Guess what? It worked, and in the last two weeks he made a massive comeback earning a spot on the Junior World Team and almost pulling out a spot on the Senior Pan American Team at 18-years-old on a packed team of studs.

Accessory Work – This is a very long term approach to a potential plateau. We are constantly trying to identify weak muscles, and then targeting those weaknesses with accessory work. Basically this was the entire premise of our EBook “No Weaknesses”. If an athlete has weak hamstrings and glutes, I can promise you that targeting those weaknesses will aid in overcoming weaknesses in their competition lifts.

[thrive_leads id=’9063′]

Velocity Based Training – I realize this isn’t available for all athletes, but I recommend investing in a unit if possible. GymAware.com is my go to source for velocity based equipment. You can actually get their Flex Unit for less than $500 with our code ‘MASH5’. Then coaches can test their athletes to determine a force-velocity profile in each of the major lifts: snatch, clean and jerk, squat, front squat, pulls, or any movement deemed important in a strength and conditioning program. Once velocity weaknesses are identified, coaches can prescribe sets and reps at a particular percentage for a particular velocity to overcome velocity deficits. This is the way to get really specific and crush difficult plateaus.

Tempo and Pauses – This is my favorite way to target movement weaknesses and flaws. For example if an athlete is having trouble staying over the bar in the snatch, the coach could prescribe Snatch pulls or deadlifts with 5 second eccentric contractions (aka lowering phase) and/or pauses at the knee or any other trouble area. Remember isometric contractions are by far the best way to strengthen joints at particular angles. If you have a power rack, you can pull into pins for designated periods of time to produce maximal effort for periods of time. This technique is my favorite.

Mental Blocks

At this point I have given you a number of solutions for breaking through plateaus, but there is one more issue that needs to be addressed. Sometimes an athlete will go through a block of time with certain mental blocks for whatever reason. I consider myself a mentally strong athlete, but I am not pretending to be a sport psychologist or counselor. Lately I have invested in my ability to aid my athletes with their mental approach by reading books like “Mindful Athlete” by George Mumford. Next semester in my ongoing pursuit of a PhD, I am excited to take an advanced Sports Psychology course.

The truth is that most plateaus and lack of performance is directly related to a mental block. Unfortunately there is little attention to this area by most athletes. For some reason in America, there is a negative connotation around sports psychology. Athletes believe that a focus in this area is a form of them admitting something is wrong. Is this logical? Nope!

We all know that work should be done with strength training, sprinting, relative strength, range of motion, and recovery. Therefore why do athletes believe they are 100% proficient in their mental capacity? Once again, this thought process isn’t logical. When I was an athlete, I worked with a sports psychologist, and I studied the topic on my own. Why? Well, I identified sports psychology as one of the mundane elements of becoming a great athlete that could set me apart from other athletes. I always assumed that if I mastered more of the mundane tasks than my competitors, I would increase my advantage over them more and more leading to me becoming the strongest 100kg/220lb athlete of all-time in 2004 and 2005 and pound for pound the strongest powerlifter in the entire world.

I implore all of you reading this. Sports psychology is the differentiator between good and great athletes. Since there are very few dominant athletes sport to sport, logically that tells us the majority of athletes (99.99%) need to work on their mental capacity. If you come with me to a world championship in almost any sport, you will notice one common trait amongst the champions, amazing confidence. They will be relaxed, focused, and fearless. All you have to do is look at the face of Michael Jordan when the Bulls were down by 1 with five seconds to go. Did he look scared or worried? No, he wanted the ball because he knew he was going to win the game.

Let me leave you with this question, and I am going to ask it in a way that will resonate with any athlete. When you:

- approach the barbell in a weightlifting competition for your opening snatch, do you think to yourself “please don’t miss” or “Let’s smoke this lift?”

- approach the line of scrimmage in a football game knowing the football is getting thrown to you with one second left on the clock down by 5, are you excited to win the game or scared that you might drop the ball?

- walk up to the plate in a baseball or softball game in the final inning down by one, two outs, and bases loaded, are you excited to be in this situation, calm, and focused on the task, or are you scared, sweating, and able to hear your heart pounding from your chest because you are scared to mess up?

- walk up to a golf ball on the final hole needing to sink the putt to win the US Open, are you relaxed and focused on the process of putting like any other putt or are you shaking from fear of missing the putt?

Improving Our Mental Game

If you aren’t a world champion, you know which athlete you are in the above examples. That’s ok because you can change that if you’re willing to work on it like anything else. I wrote an eBook along with Sports Psychologist Nathan Hansen, and is to date my least-selling eBook. That was an eye-opener for me in regards to most athletes and coaches’ views regarding sports psychology. No one wants to believe they need help in the area. Sad because that tells me most athletes will finish their career where they started it in regards to mental capacity. That’s an exciting fact for coaches and athletes that look to master all mundane components in his or her athletic ability. It is a component that can and will give an athlete a distinct advantage over their competition.

I think it’s funny watching athletes perfect sleep, nutrition, mobility, core strength, movement proficiency, and recovery, but then never spend one ounce of their time improving their mental game. They would be better off to neglect all the others and just focus on their mental performance. I know plenty of athletes that have gone on to be amazing due to their natural ability to dominate his or her sport mentally, while neglecting their bodies in sleep, nutrition, and recovery. My point is that mentally strong athletes can dominate without perfecting several other areas of their game. However, there isn’t a dominant athlete in any sport that is mentally weak. It’s the one requirement of all champions. I hope I got your attention because this is a magic bullet that the majority of you could use to dominate.

[thrive_leads id=’8552′]

Well, this article turned into a small book, but I feel good in the fact that I have spelled out several areas that each of you can use as a coach or athlete to crush through any plateau. If a coach’s answer to a plateau in performance is to keep on doing what you are doing, you might consider changing coaches. Now you know that there are multiple ways to break through a plateau. It’s up to you and your coach to continue trying these protocols one at a time until you break through. I promise there is a way out if you are willing to put in the work and try different protocols. If you believe that continuing down the exact same road will eventually break through a plateau, you aren’t using logic to make your decision.

Let me know if you have any questions! I hope that each of you go on to become champions in your chosen sport.